Findings on the accessibility of data and evidence

Data sharing, timeliness, and ease of access

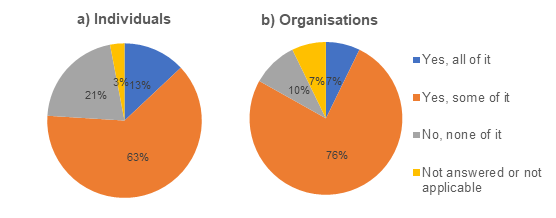

Source: UK Statistics Authority Inclusive Data Online Consultation

Difficulty accessing data was an issue raised particularly by those with research interests in education, young people, and socioeconomic inequalities. Several barriers to data access were identified. Firstly, a lack of co-ordination between different major data providers was raised by both individuals and organisations.

“Improved access and integration of data, for example the ability to combine and compare data from different government agencies.” (Disabilities Trust).

“It would be great if there were a mechanism to allow academics and public bodies to share data and construct complementary analyses.” (Individual).

Secondly, long procedures and waiting times to gain access to data were described, which may be linked to the challenges noted around lack of collaboration between data producers. Again, this was mentioned by both individuals and organisations, with an individual reporting waiting for many months, if at all, for the result

when trying to gain access to the data they needed.

The application process was described by organisations as a burden, being too long and resource intensive. One participant gave the example of Freedom of Information Requests (FOIs), which they said were very time-consuming and do not always yield clear results

(Refugee and Migrant Children’s Consortium).

Organisations noted that they needed access to sensitive data more quickly for time-sensitive projects. The National Pupil Database and the Individual Learner Records were cited by an individual as examples of data sources which require an extremely lengthy application procedure

, alongside general data on income for the purposes of socioeconomic inequalities research. The length of time taken to access data was said to have a negative effect on researchers and interested parties, limiting their ability to analyse and report on data for current and newly emerging topical issues. This was said to be caused by undoubted imbalance in power between data owners and data users in practice, despite the good intentions of legislation.

(Individual).

Participants mentioned that to access datasets from the UK Data Service they had to agree to limiting conditions, such as destruction of data after a set time-period. This was seen as particularly difficult for government bodies carrying out statutory functions on a longer-term basis. Access to the Secure Data Service (SDS) requires attending office sites, which can be an issue for organisations and individuals. The inability to access these sites, and so the SDS, was perceived as particularly problematic during COVID-19. Several participants requested more flexible arrangements for accessing secure data.

Access to some historical data was described as problematic by several individual participants, as huge amounts of historical data have been collected but there is not a clear or comprehensive way to access this data

(Individual). It was highlighted that data may not have been digitised and therefore are only available in hard copy from the individual local authority offices, if at all

(Individual).

“Comprehensive air quality data over long time frames. This data almost certainly has been recorded, but it does not appear to be accessible or digitised.” (Individual).

Organisations highlighted the challenges around exploring data which have not been analysed, meaning they had to download and analyse the raw data themselves. Additionally, data presented in traditional data tables as opposed to open data were said to be time intensive to convert into a usable format for analysis.

“A lot of time is needed to change the format of the data we use before any analysis is performed.” (Government Department).

Linked to the time it takes to access data that have already been collected in the necessary format, participants raised problems caused by lags in data series and the wait for datasets to be updated with available, already collected data. Timeliness of data availability was an area identified by organisations as needing improvement.

“Where there is a significant lag in reporting, and data are only published on an irregular basis (particularly data for which multiple years are aggregated to boost sample sizes), it would be very beneficial if the lag could be reduced, timeliness improved, and single year data provided.” Greater Manchester Combined Authority Research Team).

“ONS publishes data on energy expenditure for different household types including disabled people. Unfortunately, the most recent period available is from 2018, a two-year lag in representing the current situation.” (Scope).

Requests were made for ONS to prioritise the release of key local data from Census 2021.

“It takes far too long for local level results to emerge (based on Census 2011) and greater focus on getting these results to users could address some of the issues we have articulated in this response.” (Local Authority).

“User-friendliness” and inclusivity of access

Lack of “user-friendliness” or usability of the sites or platforms which hold public-facing data were reported as a barrier to data inclusivity. Difficulties with locating datasets and navigating websites were also repeatedly mentioned as barriers to accessibility. The ONS website was specifically mentioned in relation to these issues, with some participants noting that data release pages are unclear as to which populations they cover.

“Navigating to data can be very tricky on the [ONS] website. I often have to ‘Google’ the type of dataset I am looking for in order to find it on your website.” (Local authority).

“It’s knowing where to find the data sets as a first port of call. The ability to go to one place, that’s reliable and easy to navigate would be a huge step forward.” (Private trading organisation).

“We regularly help people navigate the ONS website and other data repositories to help them find the information they need.” (The What Works Centre for Well-being).

“Better ONS search facility with intuitive search. Search facility that provides options. [Being] visually impaired, I am not always aware I have a letter wrong, for example.” (Individual).

Whilst there was only one report of usability issues within the individual responses, this may represent a wider issue to be addressed. The lack of available data to people at risk of digital exclusion was also mentioned. As an individual participant suggested, there should be research in ALL local archives and libraries.

Different data formats, sources and multiple platforms were said to make access to data and evidence more problematic. A centralised database or more cohesion and navigation between databases was recommended. It was suggested that an improved, cohesive database such as this could be held by ONS or The UK Data Service.

“One option for increasing access to official survey data is to make more of it available through the UK Data Service’s Nesstar interactive website, although this can be slow and cumbersome to use. A better option could be to create an API [Application Programming Interface] to restricted survey data that prevents disclosure of sensitive data but allows non-disclosive calculations to be straightforwardly carried out.” (Local authority).

Mindful of the complexity of bringing all data sources across different providers together, an alternative suggestion was that it would be beneficial to have an Inclusion

section on the ONS website. This would bring together all ONS data on inclusion and personal characteristics in one place.

Participants were keen for data to be presented in a way that ensures key messages and stories from the data are clearly and easily visible, with 66 participants (35.7%) indicating an interest in improving the presentation of available evidence.

“The Ethnicity Facts and Figures website presents data in tables and bar charts that make it easy to digest the key messages and examine any disparities. We would like to see more ONS data presented in this way, as some of the issue briefing sheets have begun to do.” (Business in the Community).

The way data are often presented, as discrete categories, was said to mask any understanding of intersectionality (how various social categories might inter-connect or overlap).

“Excel data tables can be reductive for their separation of different characteristics, for example presenting “gender” and “ethnicity” side by side, rather than allowing for an overlap of these categories and intersectional analysis.” (Charity organisation).

There was a call for more interactive data, so that users would be able to examine it from different angles. Several participants felt that a tool that enables users to navigate, aggregate and compare all personal characteristics data would be ideal.

Back to top