Findings on the inclusivity of existing data and evidence

Gaps in data and evidence

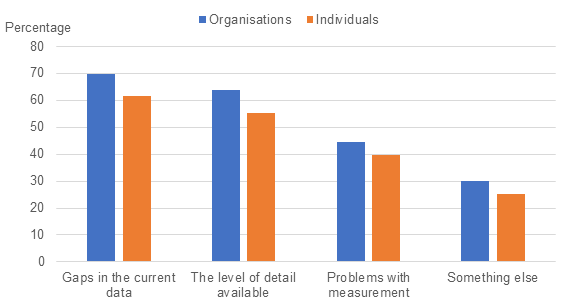

Source: UK Statistics Authority Inclusive Data Online Consultation

Further analysis of the textbox responses identified specific gaps in data and evidence relating to broad topic areas. The implications of this were reported to include hindering ability to create effective policy, to use statistics and data to improve society, and to understand the people of the UK in greater detail.

Specific gaps around equalities data were highlighted by participants including:

- digital poverty and health

- child asylum seekers and immigrants

- socioeconomic status and food poverty

- health, education, and housing inequalities

- sexual orientation and gender diversity

- carers, and those with learning disabilities

“The inability to address important questions from policy and practice on the state of wellbeing of some populations, especially people with learning disabilities, LGBT+, and unpaid carers”, meant that ”as a result… the full extent of wellbeing inequalities in the UK is not understood and may be underestimated”. This could consequently “lead to a widening of inequalities, and the design of policies that leaves some populations behind.” (The What Works Centre for Wellbeing).

There was a perception among some participants that gaps in data relating to certain personal characteristics exist because they are not prioritised or mandated

(Individual). Participants also suggested that further data be collected around the specific circumstances of populations at greater risk of disadvantage to gain greater insight into their lives and experiences. Examples of this focused on the living and accommodation conditions of disabled people; recipients of social care; and progression and attainment post-16 years of age, particularly for those in vocational courses or apprenticeships, including course opportunities and entry requirements.

Other topics participants noted where it would be helpful to collect further detail of people’s life experiences included:

- redundancies

- pupil exclusion (especially relating to Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller populations)

- prejudice

- bullying

- poverty

- hospitalisation

- mortality

- prevalence of Covid-19

- prosecutions and convictions

It was suggested that affirmative steps needed to be taken to ensure better representation of under-represented communities.

“Making sure people or groups are not excluded would demonstrate to those groups and others that many other structural conditions are ethical and fair.” (Equalities Hub).

“I am primarily interested in promoting accurate representation of those who have previously had their relationship to sex, gender and sexuality overlooked by UK data collection exercises. These people tend to identify as part of the LGBTI+ community. It is hard to answer this question when the data is not available to think of what COULD be answered (i.e. how do you predict unknown unknowns?).” (Individual).

The impact outlined of not having sufficient data and evidence around certain groups, as noted by individuals, was twofold.

Firstly, a lack of data and evidence was said to lead to invisibility and under-representation of specific groups and their experiences. It was highlighted that this lack of awareness and understanding of certain populations can lead to many questions going unanswered. This was said to make it difficult to understand discrimination based on personal characteristics and whether some groups have been systematically disadvantaged. In addition, the inability to draw robust conclusions, as well as to identify where bias exists, can yield misleading results.

Secondly, where discrimination and systematic disadvantage cannot be identified due to data gaps, this hinders ability to formulate effective responses.

“Young people who do not achieve expected or benchmark levels at GCSE are least likely to make good progress in education and employment post-16. Understanding their situation is key to reducing educational inequalities but at the moment they are quite invisible while policy and data have focused on higher achievement and widening access to university.” (Individual).

“Getting to the bottom of these evidence gaps is critical for understanding how to make more progress in addressing discrimination and of profound importance for the framing in law and policy of protected characteristics.” (Individual).

“Due to the lack of data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity in adults, it is impossible to assess inequalities in this population and to assess whether the inequalities in individual research papers are playing out at a population level. This is leading to these issues being ignored in policy and in-service implementation.” (Individual).

Different organisations shared a common view that the populations they work with are not ”nationally represented” or ”reliably identified” due to data gaps. They saw this as hindering their ability to understand and meet the needs of these groups. Examples included:

- those working with young offenders

- those dealing with young homeless people who are “not recorded anywhere in official statistics”

- migrant children

- asylum seekers

- people working with children excluded from school

In the case of migrant children, lack of data availability makes it difficult to answer questions about children and young people’s well-being and outcomes

(The Refugee and Migrant Children’s Consortium). Data gaps in this context mean that comparisons between migrant children and non-migrant children are not possible. Organisations described how gaps in data affected their ability to inform policy development and evaluate programmes and interventions.

“Without robust data, it is not possible to adequately plan for and allocate the necessary resources to ensure that government programs achieve their objectives.” (Charity organisation).

“Additional measurement and assessment are needed to capture hidden forms of homelessness and provide greater detail and disaggregated data […] Due to the difference in methodologies and reporting, there can no comparison in data or evaluation of the impact of strategies and programs.” (The Institute of Global Homelessness).

More, and better, intersectional data were described as crucial for understanding inequalities so that any inter-connections between social categories can be identified.

“It should be possible to interrogate data by multiple characteristics more readily, for example, to understand the experience of Muslim women or African-Caribbean heritage men.” (Individual).

Data gaps relating to intersectionality impact a large range of communities and individuals, including those of older ages.

“We are often not able to answer research questions regarding intersectional issues, for example how older people of particular minority ethnicities are impacted by an issue. This can mean that we are not fully able to describe inequalities between different groups of older people.” (Age UK).

Further examples of the need for more intersectional data in certain areas include science, technology, engineering, and mathematics sectors, to understand how diverse groups of women’s career trajectories differ from those of men. Also, better health data is required to understand susceptibility to certain conditions across both age and ethnicity.

Back to topGeographical coverage and data comparability

Issues relating to geographical coverage and granularity of data were commonly reported with over half of participants (54.1%) indicating it had impacted their ability to answer their questions. The geographical level of available data was the most frequently raised area requiring improvement, with 129 participants (69.7%) noting this. Issues raised in the textbox responses also included a lack of comparable data at the local, national, and international level. This reportedly made sub-national analysis difficult as and statistics broken down to a more detailed level challenging.

The importance of timely data at the local level, with sufficient demographic information to understand the experiences of different population groups, was another recurring theme across participants. Participants noted these data would enable organisations to identify and address equality issues, and to inform policy decision-making and service provision. However, they reported that analysis of existing datasets may not provide sufficient demographic information at lower level geographies due to statistical disclosure control and small sample sizes.

“There is a trade-off between granularity of data in terms of demographic characteristics and granularity of geography.” (Local authority).

Organisations highlighted a range of different areas where data gaps exist owing to a lack of data at lower level geographies. Examples given included:

- personal characteristics

- digital inclusion

- household income

- tenure

- homelessness

- transport

- the labour market

- the environment

- migration

- finance

- wellbeing

- crime

More local data was also deemed as essential to allow better service planning in areas with higher-than-average national rates of mental ill health and substance abuse.

“We would argue that there is a strong public interest and duty argument in being able to understand such areas at the local level, so we can track change over time, understand how policy choices and investment might be playing out, and compare to other places.” (Local authority).

“Reliance on national level figures may underestimate the extent of mental ill health in urban contexts such as Lambeth and Southwark in London, home to hugely diverse communities.” (Local authority).

A range of examples were also given to demonstrate the need for, and value of, geographically comparable data. Comparability was seen as vital to measure service performance across areas, identifying what is working best, and where improvements can be made.

“To look at how issues vary within constituencies and how figures for their constituencies compare to those for other constituencies to learn from areas with figures that show they are doing well” or to “compare approaches to police interaction with children across the UK in order to identify prevalence (or not) of practices that breach children’s rights, particularly in relation to certain groups of children for example Black or Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children.” (Just for Kids Law).

Some local authority participants highlighted that being able to compare city regions is fundamental to understanding relative performance levels in certain areas.

“It is also important to be able to compare the city region to national and regional averages for benchmarking purposes.” (Greater Manchester Combined Authority).

Additionally, some noted the importance of being able to compare data between urban and non-urban areas in order to understand the social and economic differences faced by residents in these areas.

Organisations discussed how, without comparable small-area data, they are unable to understand trends at a “neighbourhood level”, making it more difficult to consider the needs of different groups in that area.

“This may mean that areas which are performing less well are masked by the overall local authority average, and the experiences of different population groups are masked by the overall experience.” (Combined authority).

The lack of data at a local level was viewed as impacting both specific groups and communities in general, particularly where data gaps have affected planning and resource allocation decisions The Strategic Housing and Regeneration Service (SHARP) commented on the number of negative impacts they had experienced owing to a lack of comparable data or evidence

. For example, they had to use datasets from less robust

sources, such as data purchased from Rightmove, to answer questions because Land Registry data could not provide what they needed. They felt this can lead to less informed decision making

. Another organisation emphasised that comprehensive evidence at as local a level as possible is paramount

(Local authority).

Christian Aid also detailed the importance of comparable local data across all geographic levels for the work they do to support communities and local and national governments. They described using a bottom-up approach by understanding the communities first before aggregating to local and national levels.

Further challenges were noted in comparing data across the UK. A range of causes and impacts of issues around geographical comparability were offered.

Firstly, participants noted reduced comparability due to variations in how data are collected and reported as well as differences in the wider legislative contexts for equalities.

“There are difficulties comparing data across the UK’s four nations. Data is often collected and reported differently, with slightly different definitions used and questions asked that reflect different research and policy contexts in each of the settings.” (Association for Young People’s Health).

“The equalities guidance used to collect the data, differs between England, Scotland and Wales.” (Anonymous organisation).

Secondly, geographical boundaries are defined differently by different institutions and agencies.

“Differences in the reporting of the exact ‘locality’ of each place can make comparing data from different agencies difficult (for example, social care statistics against healthcare statistics).” (Association for Young People’s Health).

Thirdly, combining England and Wales within certain statistics (for example, healthcare) means that differences between the two cannot be easily distinguished.

“Data being available at a Wales level is extremely important as there can be major differences in the experiences of minority and marginal groups between England and Wales thereby making England and Wales combined data far less useful.” (Government Department).

There were calls from both individuals and organisations for better coordination and collaboration to improve comparability of data evidence across the countries of the UK.

“While we need to see the data broken down by devolved administrations, we also need to talk the same language as each other so that we can share best practices; we are not even at that stage yet in digital poverty, but ONS can help by providing comparable broken-down data.” (Individual).

Included in this were requests for more coordinated efforts across the countries of the UK and their statistical offices to collect and link comparable longitudinal data. This would better enable the study of inequalities across different groups and different geographical areas of the country. Some noted this would aid evaluation of whether certain policies are more effective than others.

“It is essential to collect comparable data across the UK, since policies are different in the devolved administrations, in particular in education, health and justice, and we need to know how these different policies can impact on people’s life chances and outcomes, especially in the case of groups with protected characteristics.” (Individual).

“We need to be able to make comparisons across the whole country, so need all 4 nations to be applying the same rigorous data definitions.” (The LGB Alliance).

Concerns were also raised about how the delay to the 2021 Census in Scotland would affect comparability with data from the censuses in the other countries of the UK. As the censuses in England, Wales and Northern Ireland happened amidst the pandemic, the context of people’s lives may be quite different to the situation in 2022 when the census will be held in Scotland. Additionally, it may also affect data quality due to difficulties linked to migration within the UK: this will create future problems where individuals could be missed (or double counted) if moving to different areas of the UK.

(Individual).

It was suggested that in the absence of comparable data across regions, people need to find ways of assessing comparability across the UK on a case by case basis.

“It would be lovely to have totally comparable data across regions and nation states, but that is not realistic. Instead, what is needed is excellent documentation so that individual researchers can better assess how comparable data sets are. At present we need to do this as individuals, which is inefficient.” (Individual).